Art, antiquities and adventure

Today, as it turns out, was a good day to read. Rainy, blustery, cold—perfect November weather. Perfect, as long as you didn’t have to be outside, which (happily) was the case for me for the second half of the day. The morning, however, I spent out in the elements, holding (with icy, unmittened hands) a handmade poster advertising a community food drive. The rain held off, but by noon I was cold and stiff and beyond ecstatic to hurl myself into my little silver car with the heated seats. Once back in my house, I read, and read, while the rain poured from the sky and the wind rattled the windows. I felt I deserved it.

The book that I read that blustery afternoon, once I thawed myself out enough to think, was The Sonnet Lover by Carol Goodman. I want to say that this novel is a “Gothic romance,” yet I’m not sure it fits the exact criteria. It seems that Gothic romances are technically a type of novel popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; mysteries, usually, tinged with elements of the supernatural and, more often than not, set in haunted castles or medieval ruins. A Gothic novel tends to include a woman in distress, a man who carries a burden, the presence of a ghost, dreams and nightmares, and bad weather.

The book that I read that blustery afternoon, once I thawed myself out enough to think, was The Sonnet Lover by Carol Goodman. I want to say that this novel is a “Gothic romance,” yet I’m not sure it fits the exact criteria. It seems that Gothic romances are technically a type of novel popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; mysteries, usually, tinged with elements of the supernatural and, more often than not, set in haunted castles or medieval ruins. A Gothic novel tends to include a woman in distress, a man who carries a burden, the presence of a ghost, dreams and nightmares, and bad weather.

While the timing of The Sonnet Lover doesn’t quite fit the criteria (it was published in 2007), I would say that it checks about 100 percent of the other boxes. I mean, not all the weather is bad—there are some sunny intervals and temperate, moonlit nights—but there is most definitely a scene or two set against heavy downpour and overcast skies. And there is no lack of women in distress—the principal one being the protagonist, Rose Asher, comparative literature professor at Hudson College, where (on a beautiful spring day in Washington Square Park) the novel begins. But readers do not spend long on the New York City campus and are soon whisked off by airplane to Italy, to La Civetta, a lemon-scented Tuscan villa, where Rose (we soon learn), two decades prior, found and then lost a great love.

Professor Rose’s romantic life is a key theme of this novel, but it is just one layer of a textured and ornate drama that takes the dear reader far back in time to the 16th century, when others (like Ginevra de Laura, the stonemason’s daughter) experienced passion, betrayal, heartbreak, loneliness, cruelty and longing. There are some lost sonnets, an unfolding mystery having to do with William Shakespeare and his Dark Lady, hidden treasures, nuns, dark niches from which to spy on unsuspecting suspects, ancient tapestries, greedy Hollywood moviemakers, troubled undergrads, aborted affairs, midnight gardens, secret fountains, moonlit plays, shopaholics, broken sculptures…accidents, murders, lies, revelations…this book does not disappoint.

Filled with intrigue and romance and the highs and lows of love, this book is also chock full of references to Renaissance poets, along with detailed and quite beautiful descriptions of Italian architecture, art and gardens. I know this author slightly and hear that she did a lot of research in the writing of this book, which to me makes it a few cuts above your typical “Gothic romance,” whatever that is exactly. Soliloquies and abandoned rose gardens…austere, swaying cypresses… spiral staircases and dusty archives, glasses of milky green absinthe, Romeo and Juliet, Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, dubious parentage, and a peppering of sonnets (written by Goodman’s own husband, Lee Slonimsky)…what could be better for a rainy day? Or a cold and snowy one. Pardon me while I book my ticket to Italy.

Filled with intrigue and romance and the highs and lows of love, this book is also chock full of references to Renaissance poets, along with detailed and quite beautiful descriptions of Italian architecture, art and gardens. I know this author slightly and hear that she did a lot of research in the writing of this book, which to me makes it a few cuts above your typical “Gothic romance,” whatever that is exactly. Soliloquies and abandoned rose gardens…austere, swaying cypresses… spiral staircases and dusty archives, glasses of milky green absinthe, Romeo and Juliet, Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, dubious parentage, and a peppering of sonnets (written by Goodman’s own husband, Lee Slonimsky)…what could be better for a rainy day? Or a cold and snowy one. Pardon me while I book my ticket to Italy.

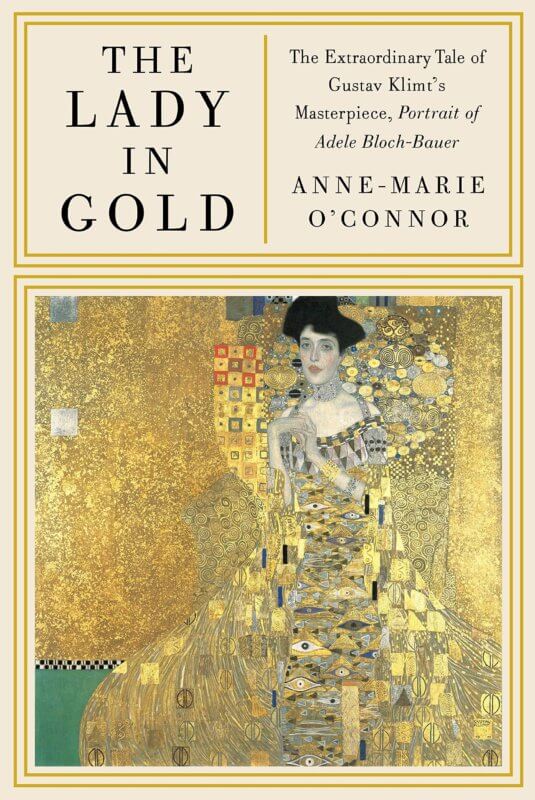

I am generally more of a fiction reader, but lately have read some gripping and worthwhile non-fiction books, one being The Lady in Gold by Anne Marie O’Connor (who, interestingly, like Carol Goodman, is a Vassar alum). You have probably seen at some point in your life the painting upon which this book is based: Gustav Klimt’s 1907 portrait of Viennese Jewish socialite Adele Bloch-Bauer.

I was told about The Lady in Gold by one of my oldest and best friends, whose husband so loved this book that, on his birthday this year, asked only that they visit together the gilded portrait at the Neue Galerie in New York City. Once there, he proceeded to spend several hours just simply…well, beholding it, my friend said. We are talking, literally, hours.

And boy, if only paintings could talk…

And boy, if only paintings could talk…

Painted during Klimt’s “Golden Phase”—in which he created a series of paintings using ornamental gold leaf and a flat, two-dimensional perspective reminiscent of much earlier Byzantine art—this gorgeous, glittering, golden portrait was pillaged by the Nazis during World War II and became, after many years, the much-coveted pawn in a decade-long dispute between the heirs of the painting and the Austrian government.

This is no Gothic romance, but that is not to say that there isn’t plenty of suspense, big fancy houses, distressed women, burdened men and mystery—but in this case, real-life. Writes O’Connor, “With the gold portrait, Adele was frozen as a symbol of the enlightened turn-of-the century Viennese woman, imbued with the opulence Klimt disdained and thrived on. The Habsburgs would borrow Adele’s gold portrait for exhibitions, to present the regal face of an empire that was modern, sophisticated and decidedly urbane.” “(Adele) is delightfully dissolute, attractively sinful, deliciously perverse,” a reviewer at the time wrote. She was the symbol of a new Viennese woman—ahead of her time, free of many of the intellectual and social limitations of women of the day, a friend to artists, poets and philosophers, a true patron of the arts.

It is shocking and troubling to read the story of Klimt’s portrait and its magnetic subject, an enlightened, articulate, highly educated woman whose life, along with the lives of her friends, family members and community, was destroyed almost overnight. A whole society—successful, progressive, prosperous, cultured—driven from their homes, wrenched from their livelihood and forced into exile and death camps—their belongings and treasures stolen, pillaged, looted, hidden and carted away by the Nazis—furniture, paintings, tapestries, sculptures, jewelry and horses…plundered…in many cases, never to be returned again, even after the war was ended.

“The public wrangle seemed a strange fate for a work of art so intimate,” writes O’Connor. “The portrait of Adele is not a field of lilies or a starry night. Here, in her naked eyes, lies a story that is more diary than novel. A painting comes from a time and place. Those who have heard the story of the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer can never again see her as a ‘lady in gold.’ Frozen in Vienna’s golden moment, Adele achieved her dream of immortality, far more than she ever could have imagined. And that,” concludes O’Connor, “is the power of art.

A beautiful painting. A mysterious model. A horrifying, complicated, sobering, eye-opening story…alas, all true. Highly recommend.